此文件來自 台灣畜產種原知識庫

https://agrkb.angrin.tlri.gov.tw

Indigenous Bali Cattle: The Best Suited Cattle Breed for Sustainable Small Farms in Indonesia

Harimurti Martojo

Laboratory of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Faculty of Animal Science, Bogor Agricultural University, Indonesia

Introduction

Indonesia has a total population of around 206 million with 4.5 million households keeping livestock. About half of the cattle farmers are small farmers. The Indonesian archipelago is a land area of 1.8 million km2 consisting of over 13,000 islands stretching from the Western tip of Sumatra to the Eastern border of Papua. The largest island, Kalimantan (Borneo), covers 28% of the total land area. Java, with only 6 – 7% of the total land area, is inhabited by around 60% of the total population and is the most densely populated island. The agro-ecological zones vary from the humid coastal wetland swamps in Sumatra, Java, South Sulawesi and Bali, to the sub-humid and semiarid dry land in the eastern part of Java, Sulawesi and most of the Nusa Tenggara islands. There is a wetter to a drier climate from the west to the east. Approximately 60% of the archipelago has about 7 – 9 consecutive months of rain in the wet season and less than two months with no rain in the dry season. The eastern islands have the lowest rainfall with the dry season varying from 3 to 8 months. The average temperature stays within a constant range differing in only a few degrees centigrade between the hot and cool months. The farming systems are regulated more by rainfall than temperature. The plantations and food crop areas are located primarily in the western wetter regions. Extensive marginal grasslands are in the drier eastern islands. Rain forest areas are found in Sumatera, Kalimantan and Papua, with limited areas on Java, Madura, Bali and Sulawesi. An alarming deforestation process is still occurring caused the illegal logging activities.

The soil fertility varies greatly, strongly affected by the climate and active volcanoes found in many of the large and small islands. The heavy rainfall causes soil erosion and high temperatures resulting in chemical weathering. The eastern islands generally have very poor soils that prevent intensive farming. The animal production systems involve both ruminants and non-ruminants. Crops and animals are integrated with the benefits associated with the complementary interactions between these products. The economic benefits of these integrated systems contribute to their sustainability (Devendra, 1993).

Animal production systems

Only three major cattle production systems will be described (Devendra et al., 1997).

1. The extensive grazing systems

These are primarily low-input-low-output systems with less opportunity for improvement through the application of new technologies:

· Native grassland grazing

· Upland forest and forest margin grazing

2. Arable crop land and pasture combination systems

The interactions between crops and animals are important in these systems, and the opportunities for interventions are significant:

· Roadside and communal grazing combined with stubble grazing

· Animals tethered or allowed free access

· Grasses, crop residues and agro-industrial by-products stall-feeding

3. Systems integrated with perennial tree crops

· Grazing under coconut, rubber, oil palm and fruit trees

In the first major system, the farmers are primarily small landholders with occasional tribal herds of a few hundred head owned by a tribal-head. In the second system, nearly all participants are small landholders. In the third system, the oldest traditional system, traditional small coconut plantation grazing is practiced. The third system is a relatively new effort, still being tried, to integrate large commercial plantations (rubber, oil-palm and fruit trees) with small landholder animal production (small and large ruminants).

Feed resources

In the Eastern islands, Nusa Tenggara Barat (NTB) and Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT), large areas of native grasslands occur, and are grazed continuously throughout the year by buffalo, cattle and goats. These grazing areas are communal and no one is held responsible for the land maintenance. Most of these areas currently have fast growing weed infestation problems, namely Chromolaena odorata. Latest unofficial observations stated that about 80% of the edible native vegetation in the grazing lands in the NTT are covered by weeds, creating serious feed resource problems for the cattle and other ruminants.

The overall availability of feed for the ruminants is probably adequate, however the problem is unequal distribution. Sumatera is over-supplied, while deficiencies can be found in Java, Madura, the eastern Islands and Papua. Trials on forage integration with perennial tree crops such as the oil palm, rubber and fruit trees are in progress.

Most cattle feed on the native forages on wastelands, roadsides, unplanted land and crop-stubble. Cattle are stall-fed year-round in systems that are more intensive. In extensive systems, cattle are herded or let out to graze in the natural common grazing areas during the day and corralled at night.

The Bali cattle breed

The Bali breed is one of the four existing indigenous cattle breeds (Aceh, Pesisir, Madura and Bali) in Indonesia. The Sumban-Ongole and Javan-Ongole may also be considered local breeds. Although no official historical records exists, it is generally accepted that the Bali cattle is the domesticated direct descendant of the wild Banteng still surviving as an endangered species in three National Wild Reservation Parks (Ujung Kulon, Baluran and Blambangan) in Java.

Taxonomy of the Banteng / Bali cattle

Many taxonomical names have been given to the Banteng/Bali cattle. Some of these names are, Bos sondaicus, Bos sundaicus, Bos javanicus, Bos bantinger, Bos banten, Bos bantinger, Bibos banteng and Bibos sondaicus (Merkens, 1926). The last two names using Bibos are based on the opinion that the Banteng belongs to a separate species (Bibos) from the other cattle groups (Bos). The Banteng are more closely related to the Gaur and Gayal. The earliest documented report on the Banteng was by Schlegel and Muller in 1836 (Merkens, 1926). They stated that the Banteng was found wild in small herds with a single bull and several cows and calves in the forests of Java and Kalimantan (Borneo). The Banteng is a large animal according to this report. The bulls have a withers height of 1.76 meters. The t’Hoen has a smaller wither height of 1.4 to 1.5 meters, and a chest girth of 2.0 to 2.1 meters. There is no recent report on the measurements of Bantengs still surviving in the Wild Reservation areas. This is because of the difficulty in catching these animals in the wild. The few samples in the Zoos in Java have no authentic records of their origin and dates of capture, casting doubt on whether they were actually wild Bantengs or just domesticated Bali cattle. The distinguishing difference between the Banteng and Bali cattle is the size and some behavioral traits.

The more recent taxonomical names adopted by the IUCN/SSC Asian Wild Cattle Specialist Group (Byers et al., 1995), naming three subspecies of wild Banteng are the Burma banteng (Bos javanicus birmanicus), the Javan banteng (Bos javanicus javanicus), and the Kalimantan (Borneo) banteng (Bos javanicus lowii). How many subspecies should be recognized and included in captive breeding programs remains an unresolved problem. There is a need to further assess the genetic and phenotypic variations within the global population of wild Banteng utilizing new DNA technologies to determine the validity of the above three traditionally recognized subspecies.

Additionally, there are unresolved questions about the purity of the genetic status of the captive population. Many founder animals for the captive populations were Bali cattle, which is the domesticated form of the wild Banteng. Because Banteng can interbreed with common cattle, there exists the possibility that zoo populations may contain genetic material from Bali cattle X Bos taurus crosses. Domestic and feral Bali and other breeds of cattle are also a threat to the genetic integrity of wild Banteng populations in the National Wild Reserves in Java.

Conservation

Both the IUCN Red Data List and the U.S. Endangered Species Act classify the Banteng as endangered. This is based on an overall decline of at least 20% over the last three generations. The Banteng is not currently listed by CITES, although the IUCN/SSC Asian Wild Cattle Specialist Group (Byers et al., 1995) is seeking to have them listed as Appendix I.

There is no immediate concern for the Bali cattle considering the current total population estimate of 2.3 million head. There is some concern about the purity because of intensive crossbreeding programs using natural mating and AI using exotic breeds that may cause extinction because of indiscriminate crossing.

Current population estimates and distribution

The Banteng

No subpopulations of more than 500 Banteng are known and only six to eight subpopulations of more than 50 Banteng are known to remain (five or six on Java). The population trend on Borneo is unknown. The Banteng populations on Java are relatively stable, although there are threats due to illegal hunting, habitat destruction and diseases from domestic livestock.

The Bali cattle

The current population estimates (of 2000) for the Bali cattle in the five major resource areas are as follows (Talib et al., 2002):

|

Resource area |

Estimate of population size (in 2000), head |

|

Bali |

529,000 |

|

NTB |

377,000 |

|

NTT |

443,000 |

|

South Sulawesi |

718,000 |

|

Lampung |

255,000 (recently added resource) |

There are other provinces with fast growing population numbers managed by small landholders. One of the most promising provinces is Southeast Sulawesi with a recent population of 300,000 head. These herds were started using small numbers of imported Bali cattle in 1923 and larger numbers during the five-year plans. Propagation was conducted through governmental owned cattle distribution to participating farmers and redistribution of the offspring to a growing number of participating farmers. This is another example of the superior quality of Bali cattle as a pioneer breed for the farming system in many new cattle production areas (transmigration projects).

There is however some concern for the negative population growth trend of 12.3% on average in due to extraction during the monetary crisis years. Measures to halt this negative trend have been taken by local governments. The total populations of the major local breeds are as follows:

|

Breed |

Population size, head |

|

Ongole |

1,033,000 |

|

Bali |

2,632,000 |

|

Madura |

1,131,000 |

|

others |

4,980,000 (including exotic and crossbreds) |

The Bali cattle have the largest number, showing it as the local cattle breed most suitable for small landholder cattle farming.

Characteristics

The Banteng is considered one of the most beautiful of all wild cattle species. They are most likely the ancestors of the domestic cattle of Southeast Asia. The Banteng are a sexually dimorphic species, with mature males being dark bluish black and cows and juveniles reddish brown. Both sexes have white rump patches and stockings. Both sexes carry horns, although they are much heavier and larger in the males. The Banteng are smaller and have a more even temperament than the gaur. There is a well-defined narrow dark stripe along the backbone, only seen in the calves and females. In bulls, the red hair on the body begins to darken at 12 – 18 months of age and by maturity, the animal becomes almost black. In castrated bulls, the black hair on the body changes to red again within a few months of castration. The body is relatively large-framed and well muscled. Adult males weigh between 600 – 800 kg, whiles adult females weigh between 500 – 650 kg. Their average lifespan in the wild is 11 years, although they can live to 20 – 25 years of age. It is very common for captive Banteng to live into their late teens or mid-twenties (Byers et al., 1995). These are humpless cattle.

Productivity traits of the Bali cattle

The Bali cattle are similar to the Banteng, differing only in size and temperament. Domestication has brought about smaller, easier to handle and docile animals. The average production traits of the Bali cattle females under the extensive farming system showed in Table 1 (Talib et al., 2002)

Table 1. Production traits of the Bali cattle females

|

Bali |

NTT |

NTB |

South Sulawesi |

|

|

Birth weight, kg |

12.3 |

|||

|

Weaning weight, kg |

82.9 |

79.2 |

83.9 |

64.4 |

|

Yearling weight, kg |

127.5 |

100.3 |

129.7 |

99.2 |

|

Weight at puberty, kg |

170.4 |

179.8 |

182.6 |

225.2 |

|

Mature cows weight, kg |

303.3 |

221.5 |

241.9 |

211.0 |

Average mature bull weights for NTB, NTT and South Sulawesi range 335 – 363 kg and the corresponding weight for the Bali is 395 kg (Talib et al., 2002). Table 2 shows the reproductive performance and milk production of the Bali cattle (Talib et al., 2002).

|

Bali |

NTT |

NTB |

South Sulawesi |

|

|

Age at puberty, yr. |

2.0 |

2.5 |

2.0 |

2.5 |

|

Calving age, month |

32 |

41 |

36 |

36 |

|

Calving interval, month |

14 |

15.4 |

16 |

15.7 |

|

Calving rate, % |

66.3 |

66.6 |

51.7 |

60.4 |

|

Calf mortality, % |

8.5 |

48 |

15 |

8 |

|

Milk prod., kg/6 month |

274.5 |

165 |

-- |

164 |

Those average figures for the cows are considered low compared to figures from the Bos taurus cattle in the intensive production systems in temperate zones. However, these figures are the highest among the indigenous cattle breeds in Indonesia, especially the calving rates. The figures in table 1 and 2 were cited from the latest article presented in an ACIAR-CRIAS organized Bali Cattle Workshop held in 2002 (ACIAR-CRIAS, 2002). The data was based on field observations and measurements in four areas from a limited number of animals. The measurements are likely influenced by the differences in environmental and management systems, thus making comparisons between these performances way not valid.

The Unique pioneering traits

A harsher environment induces smaller/lower performance in several traits such as lower calf birth weight, low milk production, lower calf growth rate and earlier calf age at foraging as well as cattle health resilience. A herd will also show lower birth rate (calving percentage/crop) and higher calf mortality under stressful climatic conditions. The smaller average growth rate and weight at different ages are also a herd survival adaptation. If necessary, a herd could revert to its wild ancestor feral/wild animal traits to survive in the wild without any human intervention. The proof of this can be seen in the feral Bali cattle populations in several small-uninhabited islands in Indonesia. The most extreme example of feral Bali cattle is the thriving population on the Coburg peninsula in Northern Australia.

The Bali cattle O. K. a species that has the ability to show different phenotypes under different circumstances, also known as phenotypic plasticity. This ability may not be beneficial for intensive management systems. However, it is favorable for the small landholder system.

Genetic improvement (Breeding programs)

Pure breeding, cross breeding and selection programs was applied utilizing local and exotic breeds in Indonesia. The following is a concise report on the efforts started in the early 19th century (Merkens, 1926; Fordyce et al., 2002; Martojo, 2002).

Ongole and Hissar breeds

Local breeds (Aceh, Pesisir, Madura, Bali, Javan-Ongole and Sumban-Ongole) were improved using Ongole bull from India. This was recorded in the 19th century using Ongole bulls and small sized local Javan-breeds (now considered extinct) in East Java. Ongole bull imports by several private plantation companies to produce larger draught cattle continued in small numbers. This was terminated at the end of the century due to rinderpest disease outbreaks in India. Massive Ongole cattle importation from India continued until 1920 on Sumba island. In 1923, the number amounted to about 1,500 head. Sumba has been a source of breeding stock for other regions since then. The Hisar breed was also imported and used in Sumatra and Northern Sulawesi.

Madura breed

Starting early in the 20th century the Madura breed was maintained pure in Madura by closing the Madura from other breeds. Trials were started to propagate Madura cattle in Java and Flores Island. However, these cattle did not thrive and a gradual change was made to the Bali breed.

The Bali breed

In 1926 the Bali breed numbered 275,000 head in Bali and 125,000 in the Lombok islands. The Bali breed was then distributed to Timor, South Sulawesi and other regions in the eastern islands. After a century of effort, the highest population among the other breeds (local and exotic) totaled 9.8 million head of cattle consisting of 2.6 million head of the Bali breed. This has proven the superiority of the Bali breed for most agro-ecological zones in Indonesia. Most of theses cattle are in the hands of small farmers. The Bali breed is the best for small landholders.

Exotic breeds

Beginning with the second five-year plan in the 1970’s, frozen semen from exotic cattle breeds was imported. Many crossbreeding programs using exotic bulls (Bos taurus, Bos Indicus and Bos indicus derivatives) or frozen semen (artificial breeding) in these regions were failed to yield desirable results. Success occurred only where zebu or zebu derivative crossbreeding was utilized. It is likely that such programs will never succeed in the harsh zones unless adequate fodder availability is assured and the farmers can afford the feed and concentrates required by the crossbred cattle. Most of the eastern island regions have plenty of grazing lands, but such lands are communal and not properly managed. Grazing on these lands is uncontrolled, leading to poor land productivity. Fodder cultivation is not in practice in these regions. The local Bali cattle survive primarily on fodder trees; grasses cut from forests, or graze in nearby forests. Fodder cultivation is not a priority for the small, marginal farmers that are the majority in the eastern regions.

Breeding programs for the small landholder farming system

The unique conditions in the small landholder cattle farming system has drawn special attention because efforts to improve productivity by introducing new technologies developed in the developed world ended in failure. New breeding approaches (Martojo, 2002; Talib et al., 2002), nutrition (Bamualim and Wirdahayati, 2002) and management programs (Fordyce et al., 2002) were suggested in the ACIAR worshop.

The most current recommendation was the “Contribution to sustainable livelihood and development; Realising Sustainable Breeding Programs in Livestock Production” (INRA and CIRAD, 2002). This recommendation is based on the presence of three production levels: Level 1 – Subsistence-based Production, Level 2 – Market-based Production and Level 3 – High-input Production. The small landholder system fits in Level 1 and requires a special method for the planning and application of various improvement efforts.

Disease resistance

It is also a known fact that exotic and crossbred cattle are less resistant to parasitic infestation and diseases in comparison to local cattle. Poor transportation, communication, and marketing infrastructure make these regions inaccessible. Extension services are therefore poorly equipped to meet the requirements for the efficient technology transfer needed for most input-intensive improved breeds. Thus, after several five-year trials plans the government of Indonesia should have been able to determine a best breeding policy for the best suited cattle breed for the small landholders system. The Aceh breed for Aceh province, Pesisir for West Sumatra, Javan-Ongole for provinces in Java, Madura for Madura province and most importantly the Bali cattle for the other provinces and the Eastern Islands and Kalimantan were considered (Borneo).

Weaknesses of the Bali cattle

Despite it’s superior qualities as a pioneer breed, this breed has weakness. The Bali breed has a unique susceptibility to the Malignant Catarrhal Fever, which is contracted through sheep as a vector. In provinces with a high sheep population, such as West Java, the Bali cattle cannot survive. Another disease unique to the Bali cattle is the Jembrana disease. This disease also has a high morbidity rate. No economically effective vaccines have been developed for these diseases. Only Bali cattle originating from Bali island (which may have a higher rate of inbreeding as a result of decades of isolation due to conservation) and non’ Bali cattle from the other areas (NTT, NTB and South Sulawesi) have this susceptibility. This major weakness has not influenced the government against using the Bali breed to improve existing populations or start new cattle populations utilizing the Bali breed.

Role of the Bali cattle in small landholder livelihood

Under harsh environmental conditions indigenous animals performed much better than the improved stock. It would not be a sustainable practice to improve the genetic potential of this breed by breeding under artificially improved conditions for higher production. Scientists and decision-makers in the regional and central government have underestimated Bali cattle. Local Bali cattle have been acclimatized over the years in these regions and have been integrated into the rural small landholder economy in marginal areas for various reasons. The important contribution of these cattle has been studied and reported as follows:

· As source of progeny (calves)

· Weight gain

· As a safe deposit (source of cash in emergencies)

· Insurance for crop harvest failures

· Draught animal in tillage work and hauling farm products

· Manure for fertilizer

The first two roles are biological production traits most studied and given the highest attention. However, the second trait may not be important in a harsh environment where survival is most important and faster growing animals may have a reduced chance for survival. In the grassland areas where crop planting is minimal, only the first and third traits are important.

Organic farming system

Environmental issues are becoming increasingly important internationally. The indigenous cattle are an important and integral component of the small landholder cattle production system. This cattle production system is essentially “organic” in nature and the most sustainable system. The farmers also prefer indigenous cattle because they are less demanding and less prone to the problems usually associated with most of the 'improved' and/or crossbred cattle.

Ecological or organic farming is seen as an alternative to chemical intensive agriculture. One of the important points in this direction would be the development of indigenous technologies for ecological and economical farming methods. It has not been argued here that crossbreeding or external genetic interventions are non-sustainable. However, the rural small landholder regions in Indonesia cannot sustain these interventions because the agricultural production method in these regions is essentially low external input in nature. Thus, any external intervention calling for input-intensiveness would cause ecological imbalances that damage the long-term sustainability. Policies re-oriented towards maintaining the indigenous Bali breed and improving their efficiency, not through external genetic intervention, but through within breed genetic improvement are required. Effectively harnessing locally available resources is also an essential requirement.

Conclusions

Based on the facts discussed in this work, the Bali cattle can be considered the most suitable indigenous cattle breed for the low-input, high stress production system still practiced by millions of families in Indonesia.

References

Bamualim, A. and Wirdahayati, R. B. 2002. Nutrition and management strategies to improve Bali cattle productivity in Nusa Tenggara. In: Proceeding of an ACIAR Workshop on “Strategies to Improve Bali Cattle in Eastern Indonesia”, Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia.

Byers, O., Hedges, S. and Seal, U. S. (eds.). 1995. Asian wild cattle conservation assessment and management plan workshop. Working document. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, Minnesota, USA.

Devendra, C. 1993. Sustainable animal production from small farm systems in South-East Asia. FAO Animal Production and Health Paper 106. FAO, Rome, Italy. pp. 143.

Devendra, C., Thomas, D., Jabbar, M. A. and Kudo, H. 1997. Improvement of livestock production in crop-animal systems in rainfed agro-ecological zones of Southeast Asia. ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute), Nairobi, Kenya. pp. 116.

Fordyce, G., Panjaitan, T., Muzani, H. and Poppi, D. 2002. Management to facilitate genetic improvement of Bali cattle in Eastern Indonesia. In: Proceeding of an ACIAR Workshop on “Strategies to Improve Bali Cattle in Eastern Indonesia”, Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia.

Martojo, H. 2002. A simple selection program for smallholder Bali cattle farmers. In: Proceeding of an ACIAR Workshop on “Strategies to Improve Bali Cattle in Eastern Indonesia”, Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia.

Merkens, J. 1926. De paarden en runderteelt in Nederlandsch-Indie. Landsdrukkerij-Weltevreden, Nederland.

Talib, C., Entwistle, K., Sirega, A., Budiarti-Turner, S. and Lindsay, D. 2002. Survey of population and production dynamics of Bali cattle and existing breeding programs in Indonesia. In: Proceeding of an ACIAR Workshop on “Strategies to Improve Bali Cattle in Eastern Indonesia”, Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia.

|

|

|

|

|

|

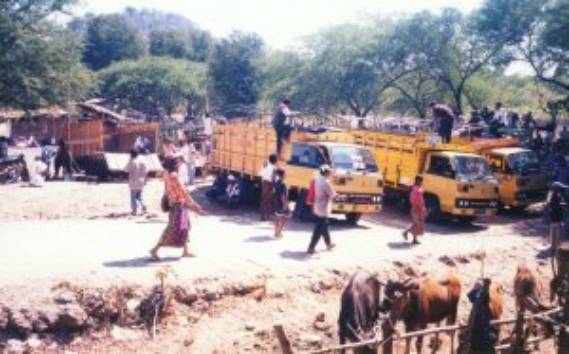

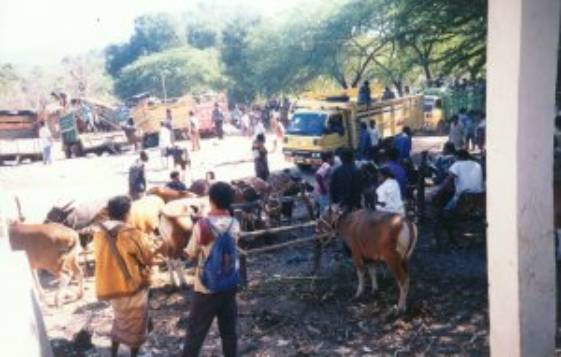

Fig. 1. A traditional Bali cattle market near Kupang, the capital of Nusa Tenggara Timur Province |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

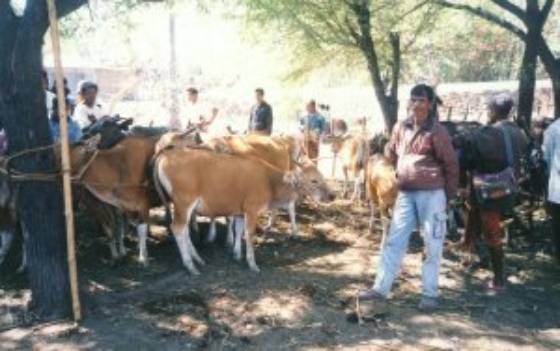

Fig. 2. An adult Bali cattle |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Cattle market and yellow trucks, transportation tools, in Kupang traditional Bali cattle market |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4. An adult Bali cow |

|

|

此文件的網址 :

https://agrkb.angrin.tlri.gov.tw/index.php?page=3265