此文件來自 台灣畜產種原知識庫

https://agrkb.angrin.tlri.gov.tw

Image of Taiwan Cattle

Yuan-Hui Chiu

The Center of General Education, Kao-Yuan Institute of Technology, Kaohsiung, Chinese Taipei

Introduction

Water buffalo and cattle might look slightly differ in their appearance or in biology classifications, but Taiwanese did not consider any culture difference between them seriously. Cattle and buffalo share the same character, “牛”, in Han dictionary. Therefore, in the following paragraph, “cattle” were used as “牛”, if not be referred intentionally. Cattle played an important role in the traditional village life in Taiwan society and had a substantial function, economic value, culture and historic meaning. Cattle carts were used by farmers to transport goods, as a vehicle, and the cattle were even sometimes straddled and ridden like a horse. Prior to the emergence of the farming tractor commonly named as “iron cattle”, cattle were indispensable laborers in the paddy fields and sugarcane orchards. Cattle, in addition to their intrinsic value were essential players in a family’s livelihood. Taiwan’s development progressed from south to north, and was cultivated from the west to the east. As the cultivated land increased, the number of cattle increased rapidly from a few thousand to more than 200 thousand. On the Taiwan map made by Ching Dynasty, cattle were drawn with the homes that represented villages to indicate the developed areas. Cattle were therefore used as an index in the developed history of Taiwan and were internalized as a part of Taiwan culture and history. Taiwanese farmers used tilling cattle for three hundred years. Proverbs were written detailing the intimate life relationship and feelings between farmers and their cattle. Taiwanese farmers often referred themselves as cattle, thereby indicating the fundamental character of the farmer. The Taiwan Governor Headquarters looked upon the buffalo as the Taiwan image used in paying tribute to the Japanese Royalty during the Japanese Reign. A stage photograph of a Taiwan entertainment troupe performing in Japan shows the cowboy striding the ox as “coming from Taiwan”. The cowboys astride the ox and cattle carts were sighted everywhere in the village forming a particular spectacle in Taiwanese villages. Cattle’s place in the village life of Taiwan was an index that could never be overemphasized. Cattle were not used merely for labor in the traditional village. They were livelihood animals closely related to the farmer’s life. The Taiwan cattle (Fig. 1) have become a totem for Taiwanese.

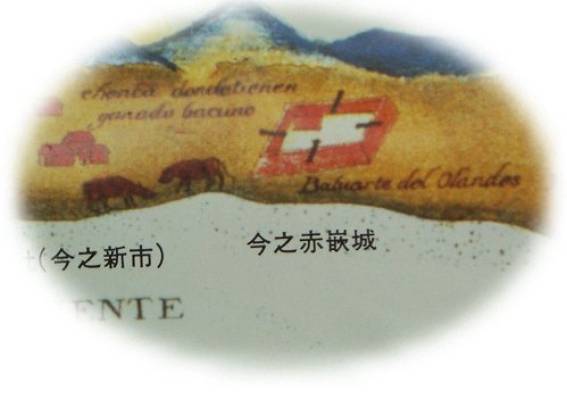

Netherlander herding cattle

Netherlanders migrated from

the Peng-Hu Archipelago to Taiwan in 1624.

The Netherlanders occupied Taiwan is merely as a stronghold for trade in

the Eastern Hemisphere. Later on,

Taiwan was discovered as a productive and potential virgin land for development.

Cultivation was begun in southwest

Taiwan. The Netherlanders began

with livestock breeding, ushering in numerous cattle and establishing the

Department of Cattle Husbandry. Then

cattle were pastured to make profits in southern

Taiwan (today Kaohsiung and Tainan areas).

Picture was painted by a Spaniard in 1626, with two head of cattle

bearing testimony to Netherlanders raising cattle in the City of Pu-Luo-Min-Che

(today Chih-Kan, Tainan, Fig. 2).

Buffalo

The Taiwanese have a legend for why the buffalo and yellow cattle differed externally. The legend has it that once upon a time a buffalo and a yellow ox were taking a bath in a brook. They suddenly heard the sound of a tiger while bathing. They both hurried ashore to put on their garments to escape. Out of impatience, the yellow ox put on the buffalo’s garment and scurried. Because the buffalo’s garment was larger, a spare piece of cloth hung around the yellow ox’s neck. This is the reason why there is a dewlap around the yellow ox’s neck. However, the sluggish buffalo is larger than the yellow ox in stature and could not fit the small garment left by yellow ox. The buffalo put it on, leaving his neck uncovered. The Kuan Yin Buddha saw and took apart her puttee near the hem (customarily called Chiao Pai) to patch the buffalo’s uncovered neck. This is why there is white skin surrounding the buffalo’s neck. When the tiger moved away, the buffalo came back the brook and waited for the yellow ox to return. The yellow ox did not return so the buffalo shouted, “Change! Change!” (“Huan” is the word “change” in Taiwanese). The yellow ox cried, “No! No!” (“Mun” is the word “No” in Taiwanese). To this day the buffalo is still shouting, “Huan! Huan!” and the yellow ox is still crying back “Mun! Mun!”. The buffalo was once the major draft animal used by farmers to cultivate rice and greatly appreciated by Taiwanese before the “iron cattle” (farming tractor) arrived (Fig. 3).

Yellow ox

The yellow ox is strong in body and docile in nature. It is light brown or brown in color (Fig. 4). The male yellow ox is rather stout at the shoulder and rhombic muscle whereas the female has a slender rhombic muscle. The adult male yellow ox weighs about 340 kg. The adult female weighs about 250 kg. The yellow ox can plough non-irrigated fields 20 to 25 acres per 4-hour working period.

Ploughing the field

Four procedures are used in soil preparation; ploughing the field (Fig. 5), rough raking the field, fine raking the field and final mixing. The plough is the first-stage tool for scarifying the soil. Because rice must grow in soft soil saturated with water, the soil must be prepared after cultivation. Ploughing the field involves turning the soil in the lower earth levels and covering the surface soil used in the last season. By doing so, the surface soil used in the last season can recover and the rice straw and green manure are simultaneously merged into the soil to become fertilizer.

Procedure for raking the field

After the field soil is rough raked, fertilizer is sprayed once into the soil. Fine raking is then performed (Fig. 6). The farm implement used for raking the field is a rake shaped like the Chinese word “而”. The farmers in Taiwan call this rake the “hand raker”. This rake is more than 0.6 meter high, 1.2 meters wide, with 7 – 11 iron teeth. The number of teeth in the rake is increased or decreased according to the size of the farmland. There are two straight posts above the rake. Across these posts is a handle that the farmer holds. The farmer draws this tool with the ox. In doing so, the soil in the field can be raked into smaller fragments. The rake teeth collect weeds while fragmenting the soil. A piece of board is placed horizontally ahead of the rake in some districts. This board allows raking the soil and mixing the field simultaneously, saving the job of final mixing.

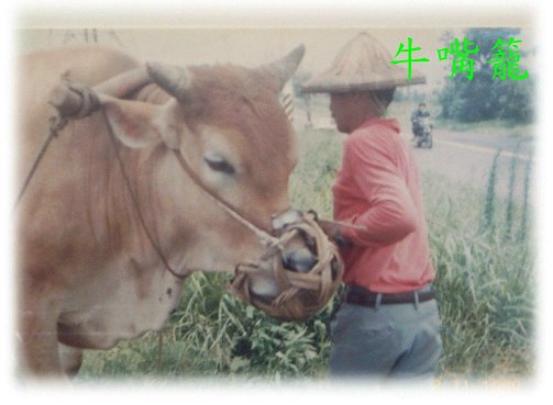

Cattle bamboo muzzle

The cattle muzzle used in Taiwan is made of bamboo strips or iron lines (Fig. 7). Muzzling can prevent the cattle from grazing on the crops ahead, ignoring tilling the soil or eating the green crops cultivated by the next-door neighbor. To extend in meaning, people call gluttonous children “cattle with no muzzle” in idioms.

Old picture of a cattle cart

The Cattle Cart has been available in Taiwan for more than 300 years. Taiwanese depended on it no less than the cars used in modern life (Fig. 8). In addition to tilling the soil and towing heavy objects, people “take cattle carts at any moment” for traveling, watching operas and so on.

Board wheel cattle cart

The greatest feature of the cattle cart was the wheels made of boards. This wheel consisted of three pieces of solid board with no distinction between the axle and the spoke (Fig. 9). The board wheel was some 5 – 6 feet high (the diameter of board wheel is 150 – 170 cm). A cattle cart with a high wheel makes much noise when the cart is traveling on bumpy roads. Uncomfortable hubbub, sounded like turning a wheel without oil, would keep going as the cart moved.

Iron leather wheel cattle cart

Improvement in the roads, the two-wheeled cattle cart was replaced by a four-wheeled cart with spoke wheels covered with an iron hoop (Fig. 10). The improved four-wheeled cattle cart could “carry more” than two-wheeled carts. However, it was no faster than two-wheeled carts on jolting roads.

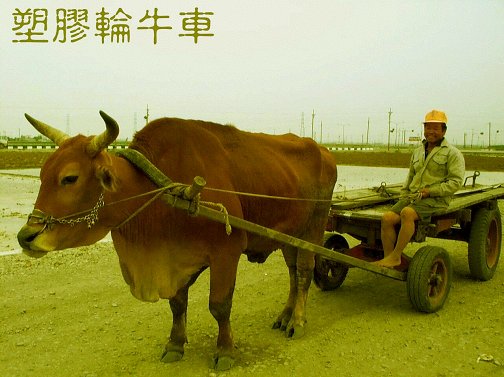

Rubber wheeled cattle cart

The rubber wheeled cattle cart appeared post World War II, replacing the iron leather wheel cart (Fig. 11). The rubber wheeled cattle cart is still in use in the Taiwan countryside today.

Cattle cart and children

Not many modern Taiwanese children had the opportunity to ride in cattle carts as their parents had (Fig. 12).

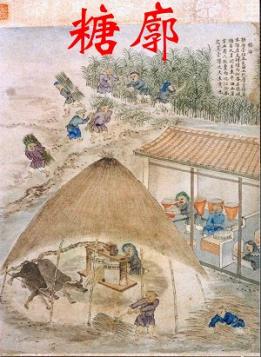

Sugar refining

The stone-grinding wheel was the major equipment for old sugar refining (simple factory of making sugar). The grinding wheel was placed in the center of a house covered with cogon grass (Fig. 13). The grinding wheel was made of two parts, a “male and female stone” over a stone floor. Large-scale sugar refineries used three grinding wheels made of granite. The grinding wheel was operated using a cow drawing the wheel. Because turning grinding wheels required a large amount of strength, several cows turn doing the chore. Sugarcane with the tails removed was placed into the space between the two wheels while the cow turned the top wheel. Sugarcane juice was squeezed out, treated and processed.

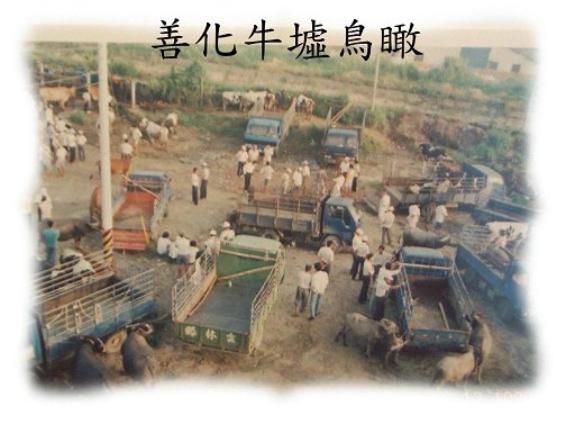

The farmer’s cattle market at Shanhua, Tainan

The “farmer’s cattle market” is an open temporary market for the regular buying and selling of cattle. There were more than 80 farmer’s cattle markets during the Japanese reign. Today only the Pei-Kang and Shanhua farmer’s cattle markets exist (Fig. 14). The fixed dates for transactions at the Pei-Kang farmer’s market in Chia-Yi are on the 3rd, 6th, 9th of each month. At the Shanhua farmer’s market in Tainan the transaction dates fall on the 2nd, 5th and 8th. The main purpose of purchasing cattle in early times was for tilling and cultivating farmland. Four steps were involved prior to selecting tilling cattle to determine if a given cow was suitable for tilling and cultivating farmland. The four steps were touching the cow’s teeth, testing the cow’s steps, having the cow pull a cart and having the cow pull a plough.

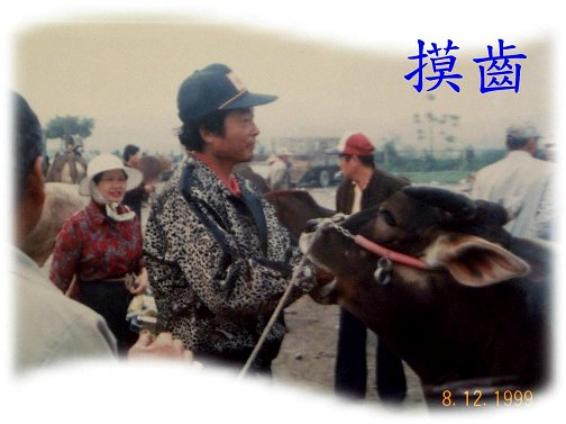

Touching teeth

Adult cattle normally have 8 front teeth in the lower jaw. A cow with less than 8 teeth is considered too young or unhealthy. The purchaser identifies the cattle’s healthy condition by counting the teeth, observing the color of the teeth and the degree of wear on the teeth to discern the cow’s age (Fig. 15).

Dragging carts

Dragging carts could be a formidable challenge for a cow. Two or three cattle carts are generally joined together in a test of cart pulling. The front wheels of the carts are tied firmly with hemp rope. The cow is then whipped to make it drag the carts without the wheels moving. The buffalo drags the carts painstakingly with its’ head nearly touching the ground (Fig. 16). The cattle harness is stuck deeply into the cows flesh. Only cattle with sufficient strength are able to drag carts with locked wheels.

Testing the cow’s steps

Specialists observe the step test. Laymen only watch this exciting “hustle and bustle”. The ox in the picture is having its steps tested. The owner leads the ox to circle around two or three times at the farmer’s market. An experienced cattle dealer or farmer will probably judge whether this ox is docile or hardworking and assiduous. If it is a lazy ox it will “conceal itself behind the plough”. If it is untamed, it will pay no attention to the owner’s commands. After observing the ox’s stride and appearance, the purchaser arrives at a decision regarding buying this ox or not (Fig. 17).

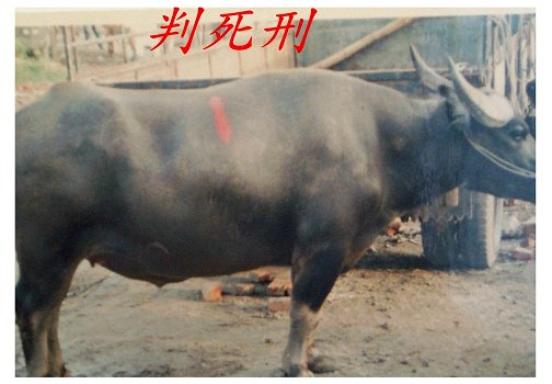

Negotiating a price and make the deal

After the procedures above, the buying and selling negotiation begins (Fig. 18). More often than not, a professional “cattle umpire” will initiate a compromise bargain on the scene. In early times, farmers went to the farmer’s market to purchase cattle for tilling fields and hauling carts. Today the purchasers are butchers who buy cattle for meat sales. After the transaction, mark was made on the back of “sold cattle” (Fig. 19). As shown in figure, there seems an innocent look on the buffalo “man as cutting-tool, cattle as beef”.

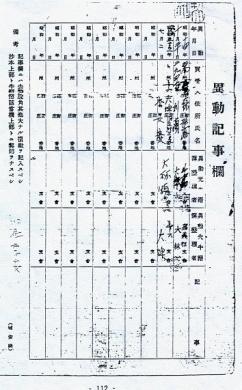

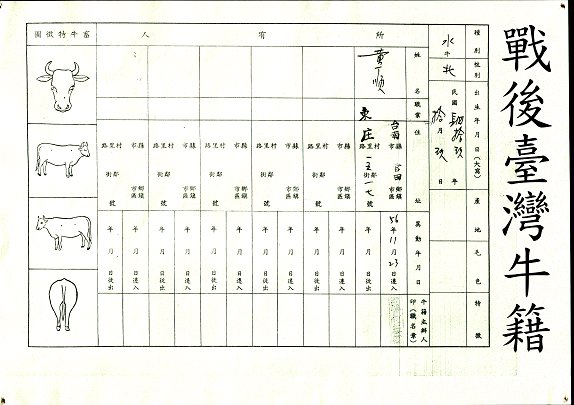

Cattle license during the Japanese occupation era

The farmer had to take his “Cattle license” card, an identification card for cattle, while leading the cattle into the farmer’s cattle market in early times. During the Japanese Occupation Era, it was stipulated that each animal must receive a cattle license identification card (Fig. 20, 21). The front side of the card showed the registered owner’s name, address and four drawings of the front, back, left and right of the cow or buffalo’s conformation. The hair whirl shape of the cattle was stamped to display the characteristics of the cattle. The overleaf side of cattle license showed the names and addresses of the previous cattle owners. The owner of the cattle had to have the cattle license with him at any time for immediate examination during the Japanese Occupation Era.

Taiwan cattle identification card after World War II

Cattle registration remained in effect long after World War II. The new cattle identification card is not different from the cattle license implemented during the Japanese occupation era (Fig. 22). Later on, the “iron cattle” (farming tractor) replaced ordinary farming cattle. Farming cattle gradually became unnecessary. The cattle identification card system was abolished in 1967.

Buffalo bath

The buffalo is heat intolerant by nature. Its temperature rises 2.7 degrees Centigrade, pulse increases 131 times and respiration increases 27 times after being exposed to the sun. The buffalo must be coated with mud or sprinkled with water to survive high heat conditions. The effects of being sprinkled with water last for 20 minutes. A mud coating could last for more than 2 hours. The buffalo takes baths to reduce heat exposure while the farmer is herding it during leisure hours (Fig. 23). The above picture shows two buffaloes gossiping while taking a bath.

Black drongo riding the Buffalo

When cattle are pastured, the Black Drongo (the name of a bird) often saddles the cattle to eat insects and other parasites on the cattle (Fig. 24). Taiwanese liken the “Black Drongo riding on cattle” to a match between ”a husband of small build to a wife of giant stature”.

Racing cattle

Modern juveniles enjoy motorcycle drag racing. In past times “village cowboys” “raced cattle” for pleasure. ”Driving the buffalo” was considered a matter of great fun! In the Ching Dynasty, riding male yellow cattle (stout yellow cattle) came into vogue. The back of the yellow ox is equipped with an ox saddle. one “could ride hundreds of miles(1 Chinese mile ≈ 0.6km) a day” on the saddled back of yellow cattle, which was equivalent to 20 – 30 Chinese miles per hour. When riding cattle, one hand controls the halter and the other hand brandishes a whip or something to coach the animal on. The children driving the buffalo in Fig. 25 is an example.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Taiwan cattle (photo at the Tong Hai University neighborhood in 1991) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Netherlander herding cattle (from the cover of Early History of Taiwan by Yung Ho Tsao, Lenking Publishing Corporation) |

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Buffalo (photo at Men-Li village, Niao-Sung Town, Kaohsiung in 1990) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Yellow ox (photo at Yuan Chang Town, Yun Lin County in 1999) |

|

|

|

Fig. 5. Ploughing the field (photo at Tung Hai University neighborhood in 1999) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6. Raking the field (photo at Kao Tan village, Jen Wu Town, Kaohsiung in 1990) |

|

|

|

Fig. 7. Cattle bamboo muzzle (photo at Tung Hai University neighborhood in 1991) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8. Cattle cart board wheel on an old painting (Photo from Map of Taiwan by Shu-Ching Huang during the reign of Emperor Kang His, Ching Dynasty) |

|

|

|

Fig. 9. Cattle cart board wheel (photo at National Taiwan Museum in 1996) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 10. Iron leather wheel cattle cart (photo at the farmer’s cattle market in Pei-Kang) |

|

|

|

Fig. 11. Rubber wheel cattle cart (photo in Yuan-Chang Town, Yun-Lin County in 1999) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 12. Cattle cart and kids (photo at Tung-Hai University neighborhood in 1990) |

|

|

Fig. 13. Sugar refinery (Fan She Tu Kao, History paintings of Natives). |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 14. The farmer cattle market at Shanhua, Tainan (photo by author in 1994) |

|

|

|

Fig. 15. Touching teeth to judge the cow’s age (photo at the Pei-Kang farmer’s market in 1992) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 16. Dragging carts (photo at the farmer’s market in Pei-Kang in 1992) |

|

|

|

Fig. 17. Testing steps (photo at the farmer’s cattle market in Pei-Kang in 1992) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 18. Negotiating a price (photo at the farmer’s market in Pei-Kang in 1992) |

|

|

|

Fig. 19. Red paint marked a “sold buffalo (photo at the farmer’s market in Pei-Kang in 1992) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 20. Cattle license (front view) during the Japanese Occupation Era |

|

|

|

Fig. 21. Cattle license (overleaf) during the Japanese Occupation Era |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 22. Taiwan cattle identification after World War II |

|

|

|

Fig. 23. Spa or tub bath? (photo at Ta An Town in Taichung County in 1990) |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 24. Black drongo riding a buffalo (photo in Pei-Tou Town in Chang-Hua County in 1993) |

|

|

|

Fig. 25. Racing buffalo (from Yuan-Hui Chiu. 1997. Taiwan Cattle. Yuan-Liu Publishing Corporation) |

此文件的網址 :

https://agrkb.angrin.tlri.gov.tw/index.php?page=3266